- Home

- Jessica Keener

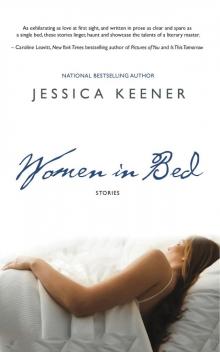

Women in Bed

Women in Bed Read online

Praise for Women In Bed:

“What we do—or don’t or won’t do—for love, in all its incarnations, is at the fiercely beating heart of this stellar collection of linked stories. As exhilarating as love at first sight, and written in prose as clear and spare as a single bed, these stories linger, haunt and showcase the talents of a literary master.”

—Caroline Leavitt, New York Times bestselling author of Pictures of You and Is This Tomorrow

“It is impossible to turn away from these beautiful and evocative stories. Jessica Keener explores the courage, vulnerabilities, and strength of women in every phase of life. No matter who you are, you will see a version of yourself illuminated in this poignant, powerful book.”

—Jessica Anya Blau, author of The Wonder Bread Summer

“Seductive, incandescent, suspenseful, and wise, Women in Bed is a masterful collection that explores a landscape of intimate love, heartbreak, and desire. Keener’s writing has a thrilling clarity. At once multifaceted and seamless, these stories map, with searing precision, the intricacies of the heart and those irrevocable moments on which a life turns.”

—Dawn Tripp, author of Game of Secrets and winner of the Massachusetts Book Award

“Haunting and profoundly thought-provoking, the nine stories in Jessica Keener’s Women in Bed are probing, unflinching portrayals of self-reflection and redemption.”

—Maryanne O’Hara, author of Cascade, a People Magazine “Book Picks, 2012”

“Demonstrates a versatile voice and ability to deliver as much exquisite detail as the stories’ brevity will allow.”

– Publishers Weekly

“An elegantly written, thought provoking book…. It is a mirror to our world, as we women think beyond ourselves, trying to bring meaning, especially the part that causes pain, to the world in which we live.”

– The Rediscovered Self

“Nine deftly drawn stories, reminiscent of those of some of the masters of the short story genre, from Katherine Mansfield to Raymond Carver.”

– BU Today

“An impressive, vividly told collection of short stories about love and intimacy.”

– Largehearted Boy

“Jessica is whip-smart, funny, and interesting, and these characteristics are reflected in her fiction. I devoured her latest short story collection, Women in Bed.”

– Ann Kingman, Books in the Nightstand

“Poignant, surprising, funny, and gorgeously written, Women in Bed is a rich collection of moving tales that will engage you from the first page.”

– Shape

“In Women in Bed, Keener leads us through a lifetime of searching. Her characters’ lives, taken together, are social commentary on the arc of relationships over a lifetime.”

– The Rumpus

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons living or dead, is entirely coincidental and beyond the intent of either the author or the publisher.

Studio Digital CT, LLC

PO Box 4331

Stamford, CT 06907

Copyright © 2013 by Jessica Keener

Jacket design by Barbara Aronica-Buck

Story Plant paperback ISBN-13: 978-1-61188-075-5

Fiction Studio Books e-book ISBN-13: 978-1-943486-05-2

Visit our website at www.thestoryplant.com

Visit the author’s website at www.jessicakeener.com

“Secrets” originally published in Sundog: Southeast Review; “Recovery” originally published in The Chariton Review, Redbook Second Prize winner; listed in The Pushcart Prize anthology under “Outstanding Writers”; “Papier-mâché” originally published in Oktoberfest, finalist award; “Boarders” originally published in Heat City Review; “Woman With Birds in Her Chest” originally published in Elixir; “Shoreline” originally published in Northeast Corridor, Pushcart Prize nominee; “Bird of Grief” originally published in Connotation Press: An Online Artifact, feature story of the month. “Forgiveness” originally published in Santa Fe Literary Review; “Heart” originally published in Connotation Press: An Online Artifact.

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever except as provided by US Copyright Law. For information, address Studio Digital CT.

First Story Plant Paperback Printing: October 2013

For Barr

Acknowledgments

As a young writer, I had the good fortune of studying with the inimitable John Hawkes and Robert Coover, my teachers at Brown University. I thank them both for their guidance and for their celebration of the short story as something transformative and enduring. Thanks also to editors Jim Barnes, Ken Robidoux, Meg Tuite, and Timothy Gager who embraced and published many of these stories. With gratitude to: the ever-entrepreneurial Lou Aronica, and book design master, Barb Aronica-Buck. For sensitive reading, thank you Leora Skolkin-Smith. To my dear friends Risa Miller, Joyce Walsh, Sherrie Crow, Susan Keith, you have graced me with your intelligence and support. For early encouragement, thank you C. Michael Curtis, Mitchell Kaplan, Steve Kronen, Laura Mullaney, Matty Bloom, Les Standiford, the Cava family, and Uncle Richard. Thank you Emma Sweeney and Noah Ballard.

I look back to the very beginning of things and thank my father, Melvin Brilliant, who read my first attempts to put words into memorable order and who, despite everything, encouraged me to write.

To my husband, Barr, and our son, Sam—love.

hope—a new constellation

waiting for us to map it,

waiting for us to name it—together

—Richard Blanco, One Today

“I listen to a few people I trust but not many.”

—Flannery O’Connor

Secrets

Every day when I walk up to her with my pencil and a pad she orders the same thing: chef salad with Russian dressing and coffee. That’s all we’ve said to each other. I nod, go get the stuff and bring it back to her. She smiles and our eyes meet. Her eyes are grey speckled: smooth stones lying next to the sea. Her skin is pale and her hair curls where it is not held back with barrettes. It reminds me of grass and wooden fences.

So far, she has never once brought a friend like most people—just a book for writing in. I’ve noticed too that she comes in at the same time. I begin to look forward to it. In this work I have time to notice these things. My job is monotonous and her visits are a relief.

As soon as she sits down, the air around her table forms a breathable shell shaped by her thoughts. She orders the salad, and when I bring it to her she eats quickly, bite after bite. But she’s not rushed. She always stays for an hour. When I pour her first cup of coffee she slows down. She asks for a refill after carelessly lipping the cold ceramic rim; and sometimes she asks for a third and fourth cup while she writes.

And I’m certain she watches me. If I look over to see how she’s doing, she’s there looking back. So I smile. She appreciates this and returns to her book. I resume placing orders, cleaning tables, wiping the counter top with a damp rag.

It’s summer now. Most of the women who come into the restaurant wear open V-neck blouses. The women who wear tight blazers are the executive types. They bring their briefcases to work. Then there are the men with the yellow pants, loafers and pink roll-up sleeve shirts—not my taste particularly.

My friend wears dungaree jumpsuits without sleeves—not my taste either—but her manners are. I like the way she sits at the table unconcerned that she is eating alone. I like

the surefootedness of her voice. She speaks directly. Her eyes focus on me as if she knows who I am. Few people do.

Most people just comment on my hair. It’s saffron gold and twists along the small of my back below my waist. I braid it for work. Even so, it gets in my way when I try to yank overstuffed bags of trash out of the barrels that contain them.

She is about the same height, same weight as me, but my arms are softer and her walk has more purpose. Anyway, I have this urge to follow her when she walks out the door each day and starts down the street. I consider it when I am scraping dirty plates or counting dimes and cents at the register.

Today she nods her head at me in the middle of her salad.

“Why are you working here?” she asks.

“Paying rent.”

“You’re miserable,” she says. “I’ve seen you biting your lip. Your left hand is trembling.”

“I’m recovering from suicidal tendencies,” I answer, testing her response.

She smiles back in a way that is very pleased and approving; so I leave again and get on with my chores. I remain cryptic. I have never opened easily to people.

At the end of her lunch hour, I return with her check and again she smiles. I don’t even look up to watch her walk out because I know she’ll be back.

The following day I’m ready with her meal when she comes through the door.

“Why don’t you meet me tomorrow after work?” she says. “We’ll talk.”

I peer inside her, pull back and scan the rest of her face.

“Fine,” I say. “I’ll wait for you here.”

I go over to a booth and take orders from three good-looking men. They all have dark eyes, plump mouths.

“Who keeps you busy after work?” one of them asks.

“Three men,” I joke. “More than I can keep track of.”

Their eyes widen and their Adam’s apples bounce up and down as they all laugh.

At four-thirty, I go into the bathroom, unbutton my uniform and slip on my dress. It’s red. My skin is tanned. I brush out my hair with long, exacting strokes. Outside the women are looking at me. The men are honking. They should; I feel my eyes opening to the world. Now everybody wants to jump in.

I turn onto Commonwealth Avenue and walk toward the sun burning through leaf shadows. But in no time my perspiration feels like an irritation. I stop at an ice cream store and take a cooling break. Ice cream cones are soothing. Still, two miles later my dress is wrinkled and wet. The long strands of my hair have separated into gold streaks down my arm. Even the hallway of my building, which for a moment is cool and dark, grows hot. Nothing lasts. My apartment is roasting away. My cat is too tired to greet me.

I might have known she wouldn’t show. I waited forty minutes at work, drank two cups of coffee and left.

“I wasn’t feeling well,” she says the next day. “Don’t be hurt.”

I nod. I’m furious.

“I promise I’ll come by tonight. You have a lovely face.”

Only when I pick up her empty wooden bowl do I glance out the window and see her: an image through glass moving away. She disappears where the picture window ends. So I stare back into the bowl. There is one flat piece of onion skin at the bottom. It is what I know of her.

Late that afternoon, I bend over the ice cream cooler, taking care not to bump my elbow against the sticky metal sides.

“You through?” she says behind the counter.

“In twenty minutes.”

“Good. I’ll take a scoop then.”

She sits at the table in the corner next to the wall.

“Do you have a lover?” she asks when I come out of the bathroom.

I think of him before answering.

“I did.”

We walk out into the hot air. There’s no wind along Massachusetts Avenue until we reach the bridge over the Charles where, grateful for the breeze, we stop midway to watch the sailboats. I smell her perfume of roses. The grainy stone of the bridge wall feels like a man’s cheek. The sun and sky and air, boats with their white cloths flickering, flatten against the background of which we are the focus. I have a feeling of wanting her inside me; close. Instead, I stare down at the water.

“What are you thinking about?” she asks.

“Things,” I say, turning to her.

“Like what? What’s deadened you? Look at your face. You’ve got the eyes of a ninety-year-old.”

I look back at the sailboats. The cars speeding behind us are waves bursting against rocks. Far out on the water, a boat moves as if sliding in mud, then slowly falls on its side. Its sails disappear beneath the surface. I watch the rescue boat leave from shore.

“I’m not dead,” I say.

“Talk to me then,” she whispers.

I feel the tips of my fingers scraping against the rock.

“You’re asleep, under the surface,” she continues.

“What surface?”

A car honks at us. The smell of the water is again lost in the traffic’s exhaust.

“Let’s move,” I say. She seems to photograph my mind. I don’t know if I like it.

“Listen,” she persists. “Where have you been the last few years?”

“Places I can’t rattle off standing on a bridge.”

“Don’t waste your time. You’ve wasted too much of it.”

That’s when she pivots and walks in a straight line toward Marlborough Street. I stand without moving, stunned, watching her walk away. Several yards off, she stops.

“Tomorrow!” she shouts.

I don’t answer. I don’t chase after her. There are still some daylight hours left and there’s a man I like to watch in the Square. He juggles eggs and bowling pins, plates and hats.

The following day I don’t predict what will occur between us, not even her salad.

“What can I get for you?”

“Come for dinner tonight.”

“What about the bridge?”

“Tonight, we’ll talk,” she says. “No games.”

I don’t say anything.

“You’re angry,” she murmurs. “I can’t help myself. I test people.”

“I must have passed.”

“Don’t hold it against me,” she says, touching my wrist. “You’ll come?”

I nod.

She writes her name and address on a napkin, the “A” rising like a fir tree shadowing the smaller letters. The “Y” at the end of her name swirls like a smooth black whip.

Her apartment, a basement studio outside Kenmore Square, has two rooms: a kitchen and a combined living and bedroom. Overhead, the pipes hanging from the ceiling are painted white to blend with the walls. The wooden floor has been painted black. It is typical in most ways except for its lack of furniture. She touches my skirt.

“Drink something,” she offers.

In the living room there is a table just inches off the floor. A wine bottle and two glasses have been placed there. The wine is pale and dry. It sucks my tongue when I sip it. I pour her glass and put it beside her plate.

“Three more minutes,” she says coming back from the kitchen. She reaches for her glass.

“Did I tell you?” she begins. “I was living with a man for almost three months.” She sweeps her glass through the air. “The furniture was his. I asked him to leave.”

I look around for signs of him. There is an oversized shirt hanging on a nail next to the mattress in the corner.

“I’m glad we met,” she says. “I don’t like many people.”

“You don’t know me,” I remind her.

Though the heat from the oven smells good, it is hard to breathe. Her windows are high up and small.

“I’ll open the door,” she says. “And we’ll eat. I hope you like chicken.”

“Is it safe here?�

��

“There was a voyeur,” she calls from the kitchen. “In July. But my lover was here then. Now I dial the police.”

We eat slowly. I glance at the bare walls and feel the moisture gathering on my shoulders. The room is darkening. Her face dissolves into the shadows. She isn’t pretty. It is her eyes that draw me to her. We drink more wine.

“We met at a Laundromat last spring.”

I listen carefully, nodding at each word.

“He moved in a month later. It was one of those things,” she says. We both glance at the mattress on the floor. “You know, in bed most of the time or at the laundry washing the sheets. I got bored.”

“I’ve never had that problem,” I say. Her eyes are all I can see. “I dive in and don’t get out.”

“Your suicide. I can see that,” she says, nodding. “Have some more wine. Where did you meet him?”

“I was working at another restaurant.”

“And he was the owner?”

“That’s right. He owned it. That’s right.” I wait for her to fill my glass. I feel her sponging knowledge from my brain. I don’t want her to stop now.

“And so?”

“Every night he stood at the bar and talked to me when I came over to order drinks. He liked to chew on a straw when he talked. He was sly. I think it was a prop to show off his tongue.”

She licks her teeth. “That was it?”

“No.”

“Well?”

I swallow more wine.

“I hate cowboy clothes,” I say. “They looked good on him though—dungarees and pointed boots. ‘Aren’t you lonely?’ he’d ask.”

“What’d you say?” Her voice demands. “You told him you masturbated thinking of him.” She coughs, laughing to herself. I wait for her to come back to me. She empties her glass, thrusting her chin into the dark; then she crosses her legs and grins.

I try to ignore her behavior and continue. “On Saturday nights, a few of us stayed late drinking and talking. One night I stayed after everyone else had left. We were alone. I was drunk. He was chewing on his straw.”

Women in Bed

Women in Bed Night Swim

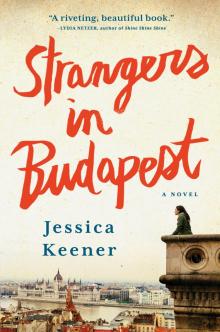

Night Swim Strangers in Budapest

Strangers in Budapest